Codex Porfirio Diaz

About the Codex

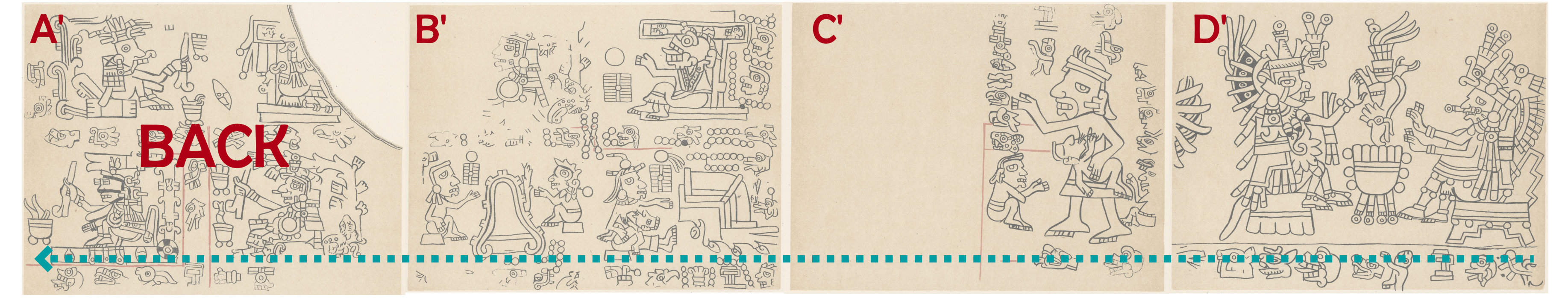

Antiguedades Mexicanas: Textos describes the original Codex Porfirio Díaz as a pre-Conquest Cuicatec manuscript painted on a long strip of deerskin measuring approximately 4.7 meters in length and 16 centimeters in width. Folded accordion-style into a screenfold book, the codex is painted on both sides, creating a total of forty pages. The Junta Colombina interpreted the manuscript as both a historical codex and a calendar, understanding its imagery to depict the pilgrimage and eventual settlement of a Cuicatec group within what is now northern Oaxaca, historically part of Zapotec territory.

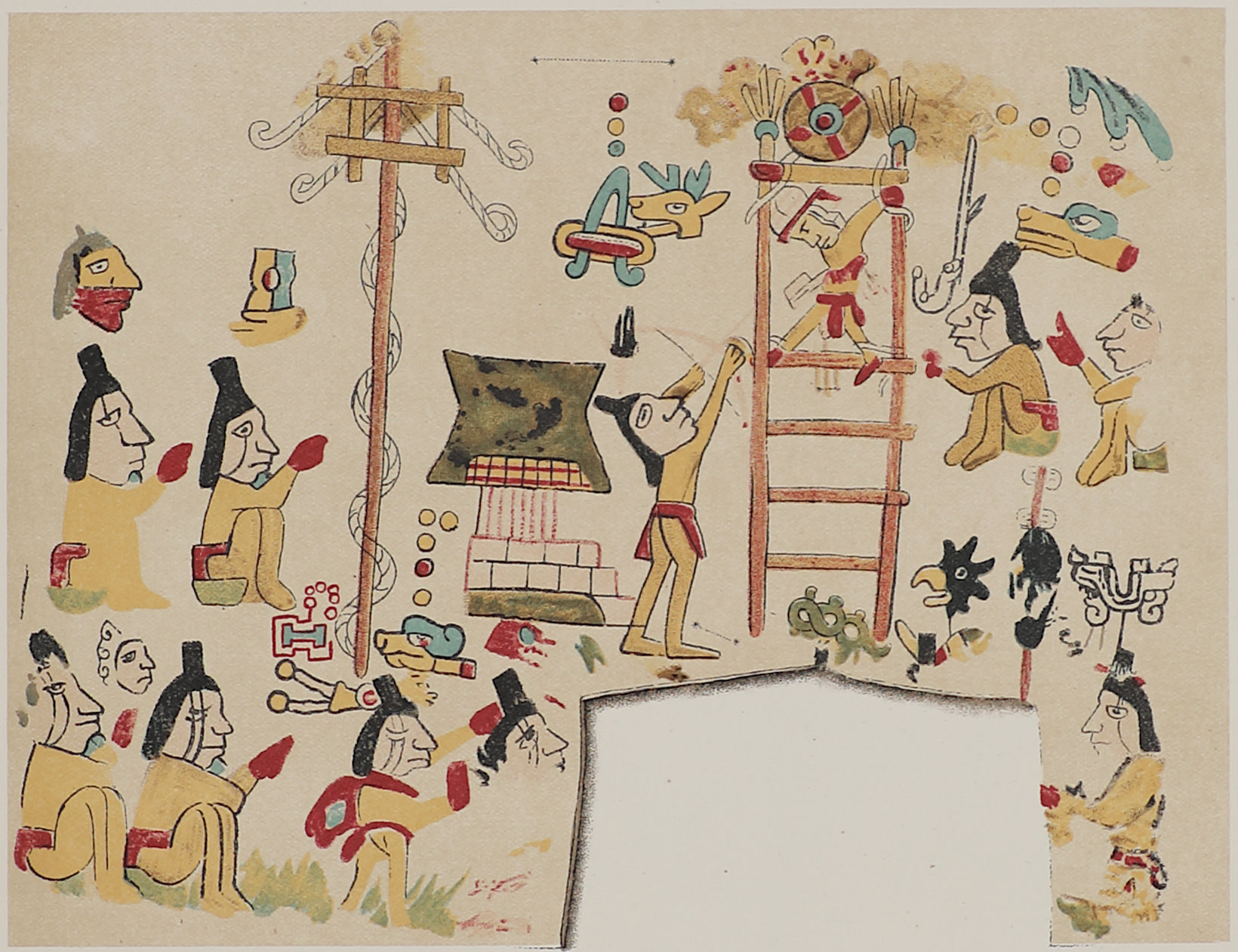

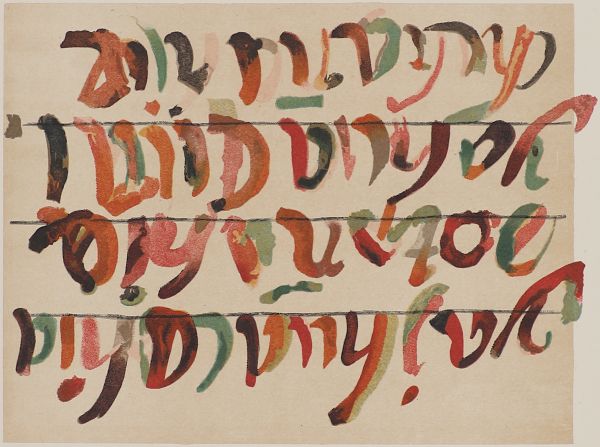

More recent scholarship has offered a narrower and more localized interpretation. Hunt (1978) argues that the historical codex documents events from a brief historical period in a small area of the Cuicatec District, focusing on a pre-Conquest conflict over water rights along an irrigation stream. The calendar on the back is said to be a religious text of calendric counts, rituals, and mythic ancestral beings or deities, painted in black, white with occasional red lines as demonstrated by the image to the the right.

How to Read This Codex

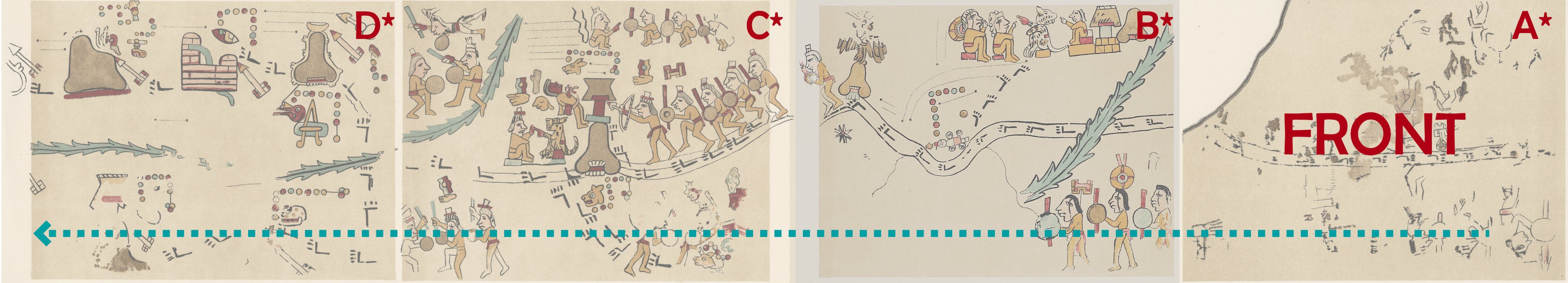

The Codex Porfirio Díaz is read from right to left across the folded screen. Once the end of the front is reached, the strip is turned over and reading continues on the back, again from right to left:

Codex Porfirio Diaz as Codex Yada

The manuscript now known as the Codex Porfirio Díaz received its name in 1892, during commemorations of the four-hundredth anniversary of Columbus’s voyage. Attaching the president’s name to an Indigenous manuscript was a deliberate political act, aligning Mexico’s pre-Hispanic past with Porfirio Díaz’s modern regime at a moment when the nation sought international recognition and legitimacy.

Jansen & Pérez Jiménez suggest that place-based names such as the Codex of Tututepetongo or the Codex Yada be used to foreground the codex’s Indigenous origins and local historical context.

Comparing the Original and the 1892 Reproduction

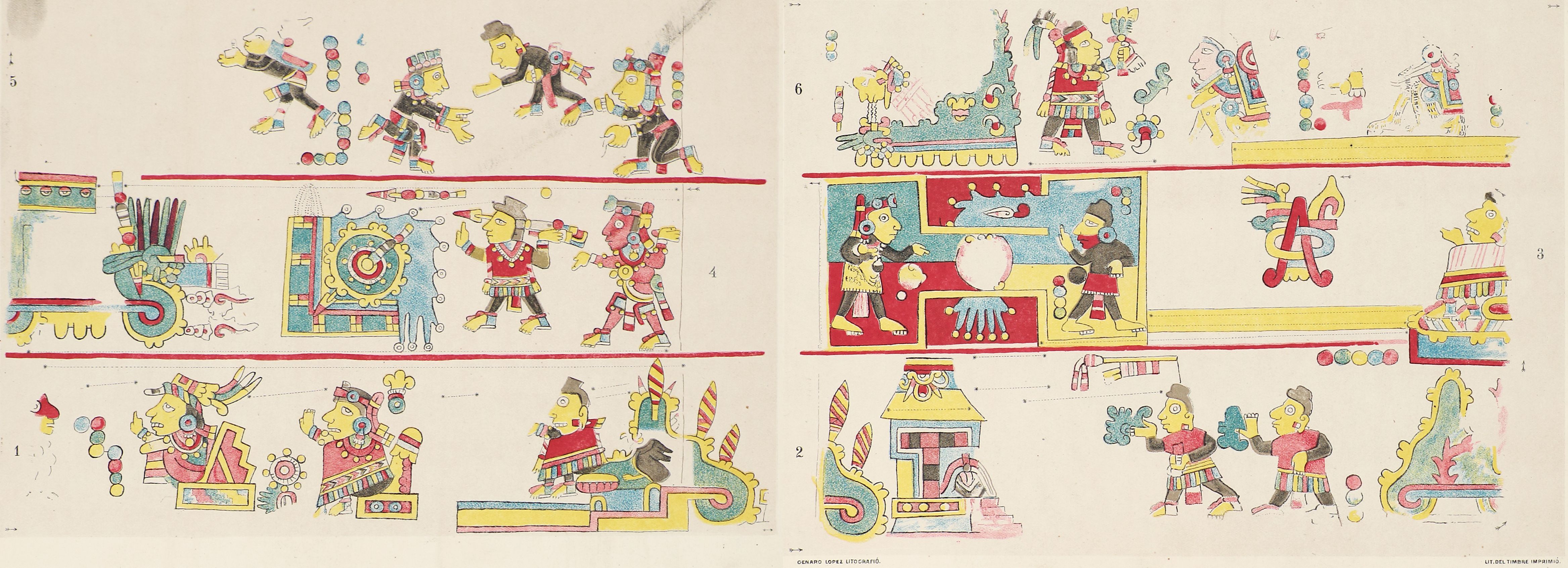

When the Junta Colombina reproduced the Codex Porfirio Diaz in Antigüedades Mexicanas (1892), they transformed how the manuscript was read and understood:

- The original folding screen was designed to be unfolded and viewed as a continuous narrative, while the reproduction was bound as a book, encouraging a page-by-page, European style of reading.

- By adding arrows and numbered panels, the Junta Colombina made the codex easier to read for nineteenth-century international audiences. These interventions helped present Mexico’s Indigenous past as intelligible, ordered, and scholarly, all qualities that supported Porfirio Díaz’s efforts to promote Mexico on the global stage as a modern nation rooted in ancient civilization.

- Similar to the Codex Colombino, this reproduction also omits Zapotec glosses present on the original codex, replacing them with asterisks.