-

Score title

-

For Zitkála-Šá

-

Composer

-

Raven Chacon

-

Program note

-

In 2005, I was a member of a small cohort of musicians and composers self-named the First Nations Composer Initiative. This group was led by prominent Rosebud Lakota singer Georgia Wettlin-Larsen, and our purpose was simply to convene, to learn that each other and our work existed, to discuss and assess our positions in the field of so-called contemporary serious music, and to find ways to expand our small community of North American Indigenous composers. The late revered Quapaw composer Louis Ballard, also part of our cohort, was recognized as the American Indian who paved the way for a Native presence in the field. As he sat and convened with us, I began to wonder: Surely, there must have been others before him–American Indians composing in the language of Western classical notation and using the instruments associated with the orchestra. If they existed, did their music survive?

It was in this search that I came upon mention of a Yankton Dakota woman named Zitkála-Šá, born in 1876 and living four decades into the next century. Her biography as a composer was little known. An opera, titled The Sun Dance Opera (1913), was linked to her name, but there was minimal writing about the work. As I researched, I learned that Zitkála-Šá (whose name translates to “Red Bird” and was also known under the white name of Gertrude Simmons Bonnin) was not only a compelling figure of American Indian history but a commanding presence in all corners of the country in the early twentieth century. Zitkála-Šá was a violinist and a composer as well as a poet, a short story writer, a political activist, a music teacher, a language translator, and, importantly, a trusted leader to many tribal communities still fighting the encroachment of the United States of America.

Zitkála-Šá was born and raised on the Yankton Indian Reservation in South Dakota and sent to a missionary boarding school in Indiana while still a child. In this separation from her elders and community, she found her traditional ways gradually being replaced with the inverted protocols and imbalances of the white world. But in boarding school, she also gained the knowledge of the piano and the reading and writing of black dots on five lines. She was forced to learn English, but her decoding of her kidnappers’ language led to a practice of writing narrative fiction and autobiography, poetry, essays, and political speeches, some of which were published in national periodicals (the Atlantic Monthly, now the Atlantic, and Harper’s Monthly, now Harper’s Magazine) by the time she was twenty-five. Her writing is fierce. It is not the privilege of retrospect we have today when we critique the early church, or residential schools, or other violent institutions of yesteryear; instead, it reads as though written from the point of view of one clawing their way out from inside the stomach of the beast.

By 1915, Zitkála-Šá was known nationally as an activista and political advocate for Native peoples. She became associated with the Society of American Indians and its championing of citizenship and voting rights, later co-founding and leading the National Council of American Indians (which later served as the basis for the National Congress of American Indians), bringing awareness to Congress of injustices suffered by Native peoples. She later formed the Indian Welfare Committee in 1924. Her work set new benchmarks for American Indian rights, resonating as new policy influencing future changes in reservation and urban Native education, tribal sovereignty, environmental law, and, most importantly, broad advocacy for all the tribes in the US and beyond. Zitkála-Šá facilitated internal pan-Indian political relations–which had never been organized before–all while continuing a creative writing and musical practice and maintaining a family.

I still could not find her music, so I visited the archives at Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana, and studied the Sun Dance Opera score stewarded by Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah. I was compelled to compose a musical dedication to her exceptional life, to an artist who demonstrated direct action in all the involuntary spaces where we, as Native people, find ourselves. I began an orchestral work, for forty-three instruments, a composition and score striving to be capable of honoring the immense work and extraordinary life of this woman. I continued my research into her biography and began to understand that Zitkála-Šá’s life was not without controversy. Her advocacy and stances on voting rights, religious freedoms, and residential schools were the source of some critique from Native people in her time, and still today, when benefiting from the distance of retrospect. I understood that the gains Zitkála-Šá fought to bring Native people can be considered an “opting in,” becoming a collaborator of the country that has tried to exterminate us. I questioned if the appropriate expression for a Native man to tell the complicated story of how Zitkála-Šá navigated the early twentieth century.

From where we sit today, my questions became: Has the story changed? Have the barriers of Red Bird’s day been eliminated between then and now? Have our efforts in the continued fight against injustices become clearer, and more unified than in Zitkála-Šá’s years? I began to think about friends and colleagues–Native musicians, composers, and scholars–who are doing important work in the field of new music. They all happen to be women, and, additionally, each has other, far-reaching extensions to their work, including education, activism, research, and leadership in their respective communities. I began conversations with each of them about how they, as Indigenous artists, are navigating the twenty-first century. I decided that the proper dedication to Zitkála-Šá was to composer new works for these musicians, composers, and scholars instead.

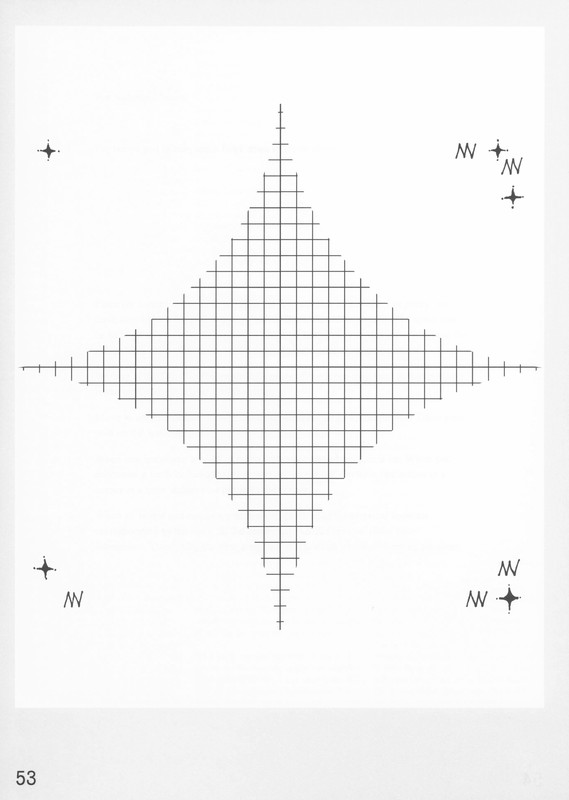

These new scores are a kind of portraiture, not merely showing who their contemporary figures are but acting more as graphic, musical transcriptions of how I describe the work, music, and otherwise of these thirteen artists. These portraits of Laura, Cheryl, Suzanne, Barbara, Jacqueline, Autumn, Heidi, Ange, Joy, Carmina, Olivia, Candice, and Buffy do not endeavor to be instructive or prescriptive, although they are opportunities to perform. They can be an invitation to retrace the steps of their subjects, as many of them incorporate a feedback loop of learning within their design. When listening to and analyzing the music of The Sun Dance Opera, one grasps how Zitkála-Šá could not notate the sounds of her traditional songs within classical notation systems. The limits of that written system cannot relay the information of the complex keys and modes of the sung Native voice, nor the fluidity of time inherent in Indigenous musics. The diatonic staff reduces all tribal music to an Indianist sound, easier digestible to white ears. A graphic score can resist the history of Western notation, and with that can eliminate normalization and assumptions of time that influence how we see the universe and whoever created us. Each score needed to fit onto one letter-sized sheet of page, as this is the physical form that also contained most of Zitkála-Šá’s work, beit poetry, music, prose, or letters of legal petition to the federal government.

In these scores, one may see a map, guiding us to worldviews that never doubted that women could be leaders. In many of these prompts, there is a duality of identity, becoming an obligation to perform two (or more) actions at once, at different speeds, and sometimes actions that are physically in conflict with others. On these pages, there is a filtering, a decoding, and mediation of speed, and a regenerating of what was lost. By following these lines, paths of agency are acknowledged and celebrated. These lines and circles and arrows and dots request that their performers have a clear aim, yet as scores provide an opportunity and potential to radiate and wander. Everyone who encounters this set of scores is invited to perform them, to better understand where they have been and where they are headed, and to cindider all the sites of conflict they are placed between.

If we see Zitkála-Šá as a woman who oscillated between two worlds, the question becomes: What is the sound of this oscillation?

Raven Chacon

Raven Chacon